Deuterium Isotopes in Water & Connections

In researching water and water cycles, I learned about hydrogen isotopes in water, which created a connection to my theory about the connection between living beings over time through the flow of water. I had made some notes in my visual diary which I mentioned in an earlier post however I wanted to clarify the importance of deuterium in informing my work.

The predominant isotope of hydrogen is protium; it only has one proton in its nucleus, whereas deuterium has one proton and one neutron. Due to its slightly different physical characteristics from protium, deuterium is significant in water formation on Earth. The ratio of deuterium to protium in water can change depending on several variables, including the temperature and environmental conditions when the water was formed. Scientists can learn more about the processes that led to the formation and evolution of water by analysing the isotopic composition of water samples from various locations and eras. According to a study by Cleeves et al. (2014), some of the water on Earth is older than the sun and even the solar system. This primordial water, originating more than 4.5 billion years ago, makes up 30-50% of the water on Earth. That water has been flowing through the hydrological cycle (water cycle) for billions of years. The water cycle is the process by which water moves continuously from the surface of the Earth to the atmosphere and back. Deuterium can be found and tracked throughout this cycle. Deuterium can be found in all forms of water, including the water in our bodies. Deuterium accounts for 0.02 per cent of the hydrogen in seawater, and other water sources have different natural deuterium levels. When living beings consume water, they also ingest its deuterium signature or "fingerprint" that reflects the source of the water. Scientists can also determine the origin, history and migration patterns of living beings.

Hydrogen Isotopes

Retrieved 28 August 2023 from https://baike.baidu.com/pic/%E6%B0%98/7030165/1/902397dda144ad34598298ccfae81bf431adcbef2f6c#aid=1&pic=902397dda144ad34598298ccfae81bf431adcbef2f6c

Take photo of top view of vessel to relate to representational shape of hydrogen isotopes.

Connection to Practice:

Water plays a big part in my body of work. Deuterium informs this project as it is an isotope within water and is present in bodies of water and water cycles. It gives water its own fingerprint, allowing history and origins to be known. When I am thinking about how water connects living beings (bodies of water) since their existence as a species and over time through many bodies over time, deuterium is a known traceable marker that validates this. Although it cannot be seen in the algae-based bioplastic works I am making, Deuterium would be present in the water I use as it is in living beings. A study, Deuterium in New Zealand rivers and streams, by Stewart et al. (1983) showed the deuterium levels obtained from over 750 samples taken around New Zealand, which confirms it is present in different bodies of water in New Zealand. The isotopes in water (hydrogen and deuterium) are represented in the artwork by the shape of the vessels; figures of these isotopes are illustrated with 2 circles (one inside the other) which the top view of the spherical vessel looks like (circular opening inside the outside diameter of the vessel).

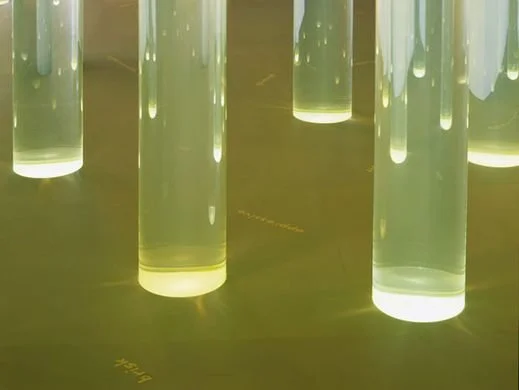

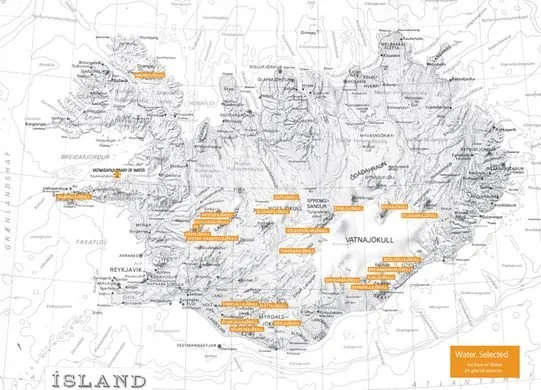

Library of Water by Roni Horn

Artist Roni Horn created a sculptural installation, Library of Water, in Iceland. It is a collection of water obtained from Icelands glaciers. Photos of the exhibition (shown below) show uniform-sized glass vials in a room. There are words about weather on the floor around the vials in English and Icelandic. Each of the vials in the exhibit has captured a sample of glacial bodies of water in Iceland. An archive of weather reports compiled from locals in and around Stykkishólmur is kept with the water collection, and voices of the local weather reporters can be heard in a small room next to the sculpture installation. The library is located where weather conditions were monitored in Iceland in 1845. I think the visual simplicity and structure and placement of the vials in the installation are quite beautiful. The water is something so important in this installation, the historical and geological significance, and it is interesting to see an artist displaying water. Analysis of the composition of the water will show deuterium levels and may be used in scientific studies too. Its a installation which has some relevance to the theory behind my bioplastic bodies of water.

Known as “Vatnasafn” in the native Icelandic, the Library of Water is a long-term project that has set out to capture the spirit of Iceland through its waters, weather, and words.

Located in a former library building built on a coastal promontory, this long term installation by American artist Roni Horn, is both an art piece and natural history collection. The piece consists of three distinct parts: One area collects audio recordings (accompanied by visual displays) of Icelandic weather as reported by the local people around the town of Stykkishólmur, where the exhibition is located, creating an interactive self-portrait of the area. Accenting this display is the floor of the main room which is made of rubber etched with both English and Icelandic words pertaining to the weather. The centerpiece of the site is the titular “Library of Water” which is kept in floor-to-ceiling clear cylinders. Each pillar standing throughout the main room is filled with water that was melted from one of Iceland’s 24 glaciers. Every tube holds the liquid of a single glacier, allowing visitors to take a sort of tour all across Iceland right in one room.

Given that the mineral and chemical content of each glacier’s melt is different, each of the over-sized vials has essentially captured a very specific portion of the country for posterity and eventually, historical interest. The Library of Water has already began to serve a preservationist purpose as it contains the melt water of the Ok glacier which has since disappeared.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/the-library-of-water-stykkisholmur-iceland

References

Cleeves, L. I., Bergin, E. A., Alexander, C. M. O., Du, F., Graninger, D., Öberg, K. I., & Harries, T. J. (2014). The ancient heritage of water ice in the solar system. Science, 345(6204), 1590–1593. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1258055

Daya, P. D. (2023, January 13). What is Deuterium? IAEA. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/what-is-deuterium

Grundhauser, E. (2023, August 20). The Library of Water. Atlas Obscura. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/the-library-of-water-stykkisholmur-iceland

Hall, H. (2020, July 6). Deuterium depleted water | Skeptical inquirer. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://skepticalinquirer.org/exclusive/deuterium-depleted-water/

Stewart, M. K., Cox, M. A., James, M. R., & Lyons, G. (1983). Deuterium in New Zealand rivers and streams. In International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) (INS-R--320). Institute of Nuclear Sciences. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://inis.iaea.org/search/search.aspx?orig_q=RN:1607083

https://baike.baidu.com/pic/%E6%B0%98/7030165/1/902397dda144ad34598298ccfae81bf431adcbef2f6c#aid=1&pic=902397dda144ad34598298ccfae81bf431adcbef2f6c